Monetization vs. Simplicity: Evaluating the Trade-Offs

When we begin a new pricing transformation with a client, we often ask: do you want your pricing strategy to focus on monetization or simplicity?

The answer we typically hear is: "Both!”

While that’s an understandable goal, it’s a hard one to achieve. The truth is, the structural elements of a pricing strategy that drive greater simplicity often pull away from monetization - and vice versa. As you build your pricing model, it’s important to recognize that these two forces sit in tension. And success isn’t about optimizing both equally. It’s about designing the right tradeoff between them.

The right pricing strategy requires balancing monetization and simplicity - not equally, but deliberately - based on your goals and your customers. And while the tradeoff between simplicity and monetization can feel abstract, it’s surprisingly easy to see when you’re ordering a burger (we’ll come back to that!) First, let’s look at what actually drives these forces apart.

Why Simplicity and Monetization Pull Apart

In pricing, simplicity refers to how easy it is for customers to choose what they want and understand what they’ll pay and how straightforward it is for teams to sell, manage, and explain. Monetization, on the other hand, describes the extent to which the pricing strategy captures the value the customer receives.

As a pricing strategy becomes simpler, it often captures less value, because there may be fewer monetizable choices, or fewer levers on which to scale price. The reverse is also true: a more granular pricing structure can better capture value, but usually at the cost of additional complexity.

Understanding this push-and-pull is critical. Because a pricing strategy designer will need to decide the maximum amount of complexity they are willing to tolerate in order to maximize monetization, or the amount of monetization they are willing to forgo to maximize simplicity. And all of this will be driven by the vendor’s priorities and customer dynamics.

The Structural Levers Behind Each Side

Certain choices in your pricing architecture naturally favor one end of the spectrum.

Levers that improve monetization tend to include:

- Granular packaging: Breaking your product into more components (e.g., multiple tiers, à la carte add-ons) lets you assign distinct value and price points to each element.

- Value-aligned price metrics: Using metrics that better align scale with how customers derive value (e.g., volume of data processed, usage frequency), even if they are less familiar, allows tighter alignment between what customers pay and what they get.

- Multiple metrics and price fences: Incorporating more metrics and categories that influence price allow an even greater degree of control over the price.

- Sophisticated price curves: Pricing structures that scale non-linearly, like bands and sliding scales, often do a better job of aligning price to value.

For example, a usage-based model might charge $0.10 per unit for the first 1,000 units, then $0.08 after that - capturing value while encouraging higher usage.

Levers that improve simplicity typically include:

- Fewer choices: Simple packaging (e.g., “Good / Better / Best”) shortens the sales cycle and reduces decision friction.

- Acceptable metrics: Relying on familiar, predictable pricing units (like per seat or per project) makes pricing easier to understand, even if it’s less tightly aligned to value.

Per-seat pricing, for example, is easy to explain and forecast - but often fails to scale with actual usage or customer growth.

- Flat or step-based pricing: Simple structures that avoid marginal cost calculations make it easier to sell, forecast, and adopt.

Recognizing which levers push in which direction gives you the control to design the tradeoff intentionally, rather than drifting into unnecessary complexity or missed monetization.

The Restaurant Analogy

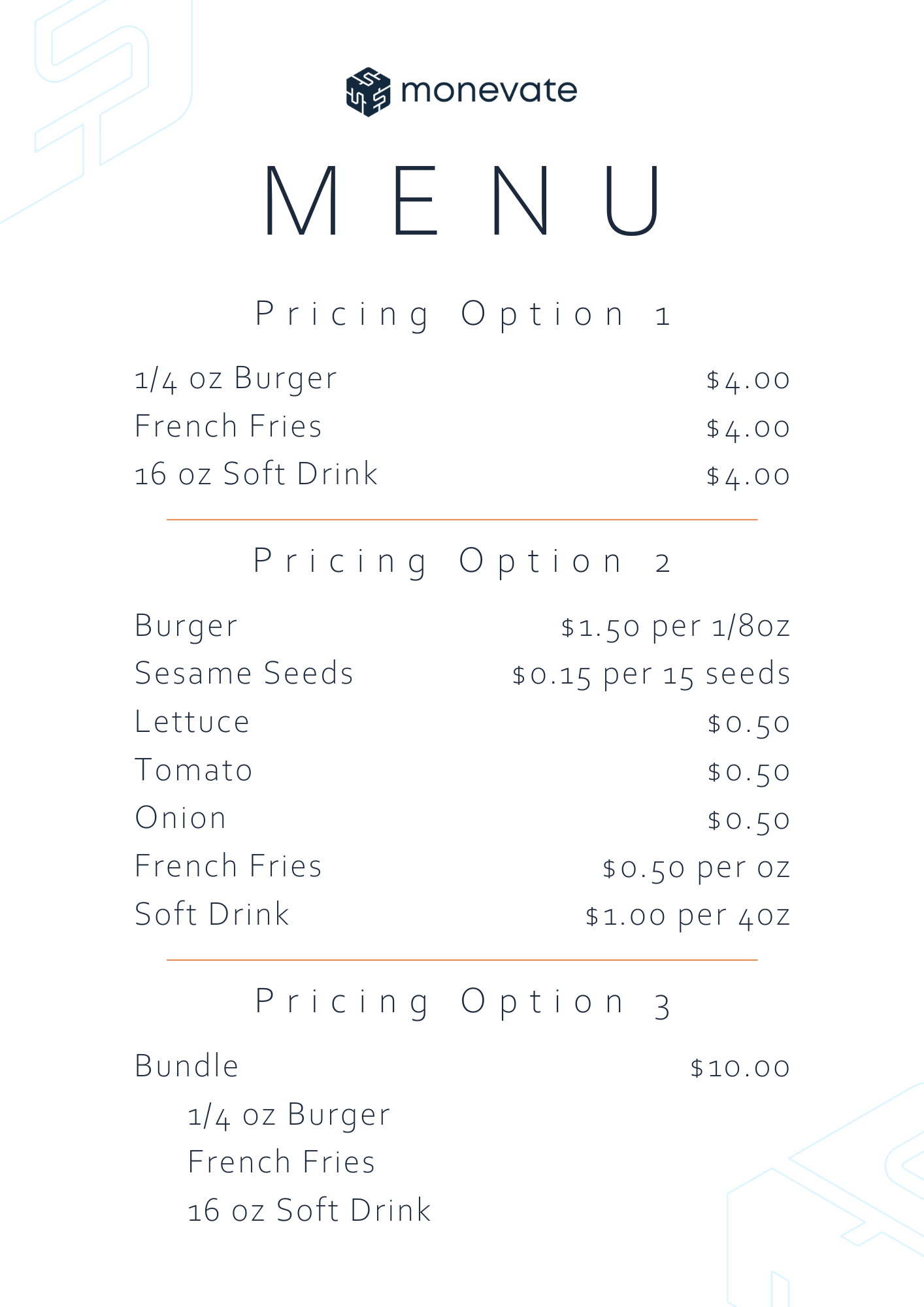

To bring this tradeoff to life, let’s return to a familiar setting: a restaurant offering three items: burgers, french fries, and soft drinks.

Model A: Flat rate per item

One of the simplest pricing models would be to charge a flat rate per item, regardless of type. Four burgers would cost the same as three fries and a soda. This is easy to calculate and easy for customers to understand, but it fails to reflect the differing value of the items. Burgers typically cost more to produce and are valued more highly by customers.

This model risks “pitching to the middle,” which can either:

- Under-monetize the burger, or

- Overcharge for fries, leading to lower sales.

Model B: Ultra granular

On the other end of the spectrum, the restaurant could adopt an ultra-granular pricing model - charging separately based on patty weight, number of toppings, and even sesame seed count. This ensures precise value capture, but:

- Turns off customers due to its overwhelming complexity, and

- Creates operational strain in tracking and enforcing pricing.

Model C: Bundled Meal purchase

A more practical approach would be to offer a bundle: burger, fries, and drink for $10. This strategy:

- Simplifies the purchase decision,

- Encourages take-up of all three items, and

- Still reflects value in aggregate, even if it smooths out some differences.

This analogy holds for software too. Simpler pricing makes it easier to buy and sell but risks leaving money on the table. More granular pricing may capture value better but can become a barrier to adoption.

There’s No Universal “Right” Balance

There’s no “right” balance between simplicity and monetization. It will depend largely on what you, the vendor, are trying to solve for.

If your main priority is to maximize sales velocity, you should lean more heavily into simplicity. A clean, intuitive pricing model removes friction and shortens the sales cycle, especially important in SMB and product-led segments.

If your focus is profitability or maximizing expansion revenue, you will likely allow more complexity to increase the degree of monetization. Granular packaging, multiple metrics, and usage-based models can help ensure each deal reflects the value delivered.

Most companies need an element of both: predictability for sales, and upside for growth. That’s why it’s critical to define your relative priorities early and design pricing that strikes the right balance.

“Simplicity” Depends on Who You’re Selling To

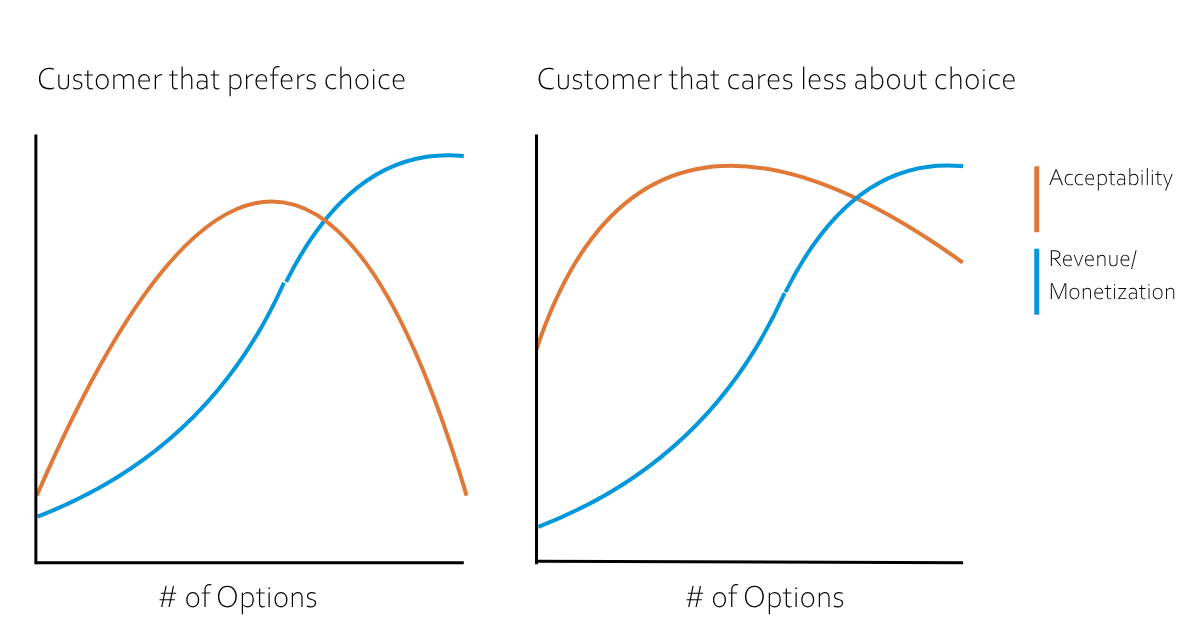

It’s also worth remembering: simplicity is not an absolute standard: it’s buyer-relative.

- Consumers and PLG buyers typically have very low tolerance for pricing complexity. They don’t have time (or interest) in comparing plans, breaking down tiers, or deciphering usage thresholds. An “acceptably simple” pricing strategy will be very simple for these buyers.

- Enterprise buyers, by contrast, often expect pricing to be customized and nuanced. Procurement teams exist to optimize spend, and they’re prepared to evaluate complex proposals if it means getting what they want. So, “acceptably simple” is probably much more complex for these buyers.

So the real design question isn’t “Is our pricing as simple as it can possibly be?” It’s:

“Is our pricing simple enough for our specific customers?”

Final Thought

To try to fully maximize both simplicity and monetization is to pursue two forces that, by definition, pull in opposite directions. The goal isn’t to optimize each independently; it’s to strike the right balance between them, based on what matters most to your business and your buyers. That’s what effective pricing strategy is: not perfection, but a thoughtful reconciliation of tradeoffs.